When planning their estates, most people focus on major assets, such as business interests, real estate, investments and retirement plans. But it’s also important to “sweat the small stuff” — tangible personal property. Examples include automobiles, jewelry, clothing, antiques, furniture, artwork, photographs, music collections, personal papers, collectibles (such as stamps, coins or baseball cards) and mementos.

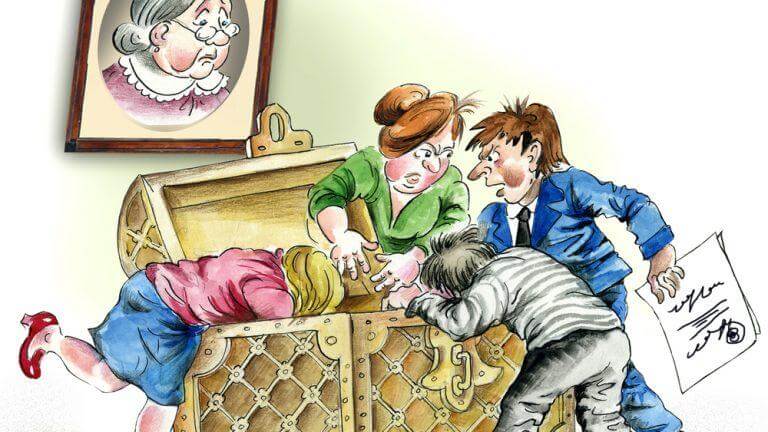

Ironically, these personal items — which often have modest monetary value but significant sentimental value — may be more difficult to deal with, and more likely to result in disputes, than big-ticket items. Distributing $4 million in stock or other liquid assets among your children is relatively straightforward. But dividing a few thousand dollars worth of personal items accumulated over a lifetime is another story. Squabbling over these items can lead to emotionally charged disputes and even litigation. In some cases, the legal fees and court costs can eclipse the monetary value of the property itself.

Create a dialogue

There’s no reason to guess which personal items mean the most to your children and other family members. Create a dialogue to find out who wants what and to express your feelings about how you’d like to share your prized possessions.

Having these conversations can help you identify potential conflicts. After learning of any ongoing issues, work out acceptable compromises during your lifetime so your loved ones don’t end up fighting over your property after your death.

Make specific bequests whenever possible

Some people have their beneficiaries choose the items they want or authorize their executors to distribute personal property as they see fit. For some families, this approach may work. But more often than not, it invites conflict.

Generally, the most effective strategy for avoiding costly disputes and litigation over personal property is to make specific bequests — in your will or revocable trust — to specific beneficiaries. For example, your will might leave your art collection to your son and your jewelry to your daughter.

Specific bequests are particularly important if you wish to leave personal property to a nonfamily member, such as a caregiver. The best way to avoid a challenge from family members on grounds of undue influence or lack of testamentary capacity is to express your wishes in a valid will executed when you’re “of sound mind.”

If you use a revocable trust (sometimes referred to as a “living” trust), you must transfer ownership of personal property to the trust to ensure that the property is distributed according to the trust’s terms. Usually this is done with a general “Assignment of Personal Property” that you complete at the time you create your trust. The trust controls only the property you put into it. It’s also a good idea to have a “pour-over” will, which acts as a fail-safe to deal with any property that is held outside of your trust and in your personal name by mistake or accident. Keep in mind, however, that property that passes through your will and pours into your trust might have to go through a probate court in what California calls a “Heggstad petition” depending on the property’s value.

Prepare a personal property memorandum

Spelling out every gift of personal property in your will or trust can be cumbersome. Perhaps you want to leave your son a painting he’s always enjoyed and give your daughter your prized first-edition copy of your favorite book. You may want to leave your coin collection, which has never interested your children, to an old friend. And so on.

If you wish to make many small gifts like these, your will or trust can get long in a hurry. Plus, any time you change your mind or decide to add another gift, you’ll have to amend your documents. Often, a more convenient solution is to prepare a personal property memorandum to provide instructions on the distribution of tangible personal property not listed in your will or trust.

In many states, a personal property memorandum is legally binding, provided it’s specifically referred to in your will and meets certain other requirements. You can change it or add to it at any time without the need to formally amend your will. Even if it’s not legally binding in your state, however, a personal property memorandum can be an effective tool for expressing your wishes and explaining the reasons for your gifts, which can go a long way toward avoiding disputes.

If you use a personal property memorandum, it’s advisable to include certain property in your will or trust, such as high-value items, gifts to nonfamily members or other gifts that are susceptible to challenge.

Get an Appraisal

Often, the value of personal property is purely sentimental, but some items have a substantial market value as well. For more valuable objects, executors or administrators are well advised to obtain a professional appraisal. An appraisal can help stave off challenges on grounds that property was undervalued in dividing the estate among its beneficiaries. This is particularly important when the executor or administrator is also a beneficiary.

An appraisal may also be required under federal tax law. For example, if an art or collectible item — or collection of similar items — is worth more than $5,000, a written appraisal by a qualified appraiser must accompany the estate tax return.

Little things mean a lot

As you plan your estate, don’t overlook tangible personal property. The dollar value of these items may be relatively low, but their emotional value demands careful planning to avoid hurt feelings, misunderstandings and disputes. Your estate planning advisor can help you include these items in your estate plan.

If you Need Help, It Would Be Our Pleasure...